OASIS

curated by Paulius Petraitis

at Meduza, Vilnius, Lithuania

On View: 18 July 2025 → 27 August 2025

Roomsheet of the exhibiton

Review in Echogonewrong

Photo documentation of the exhibtion

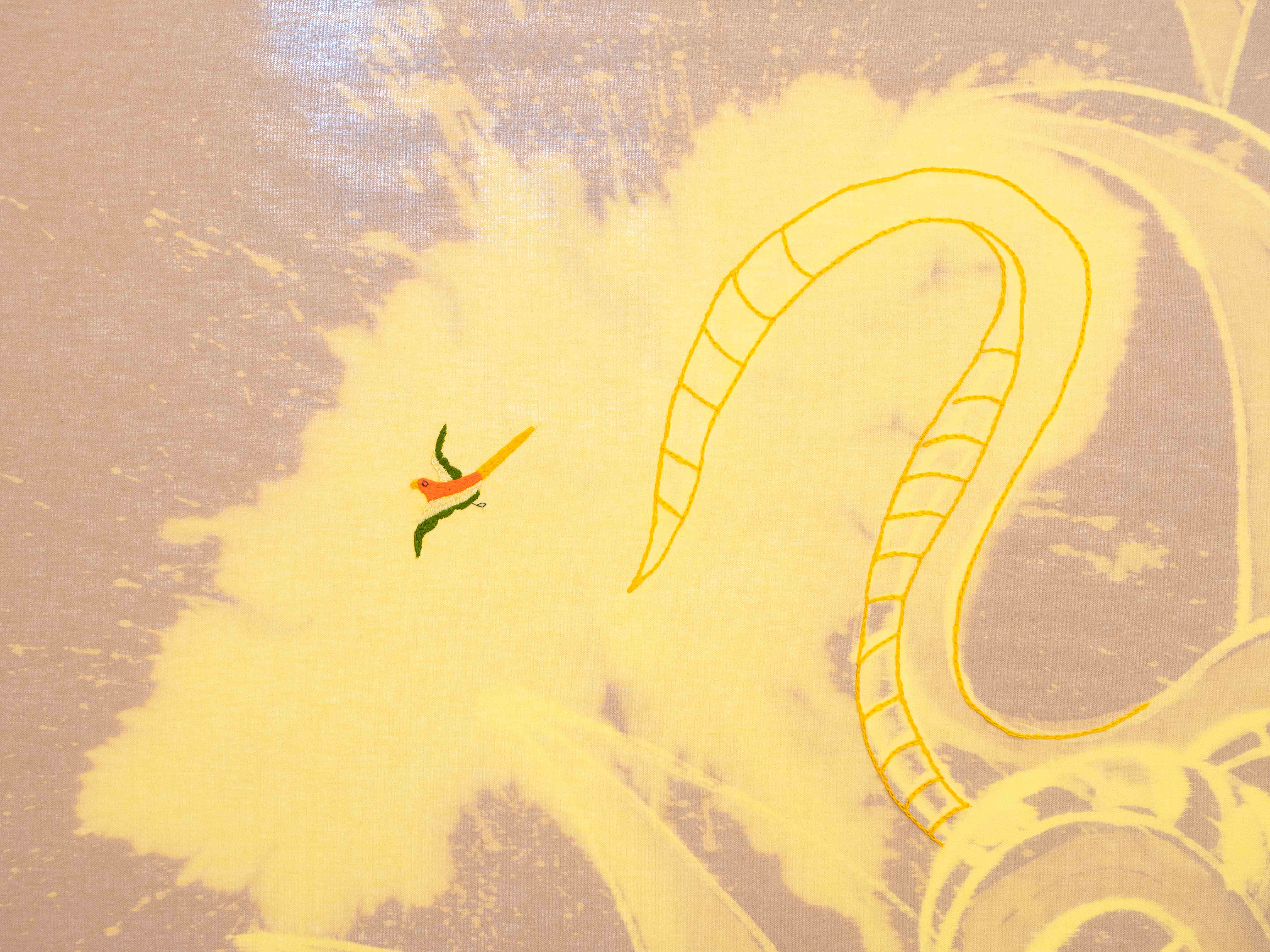

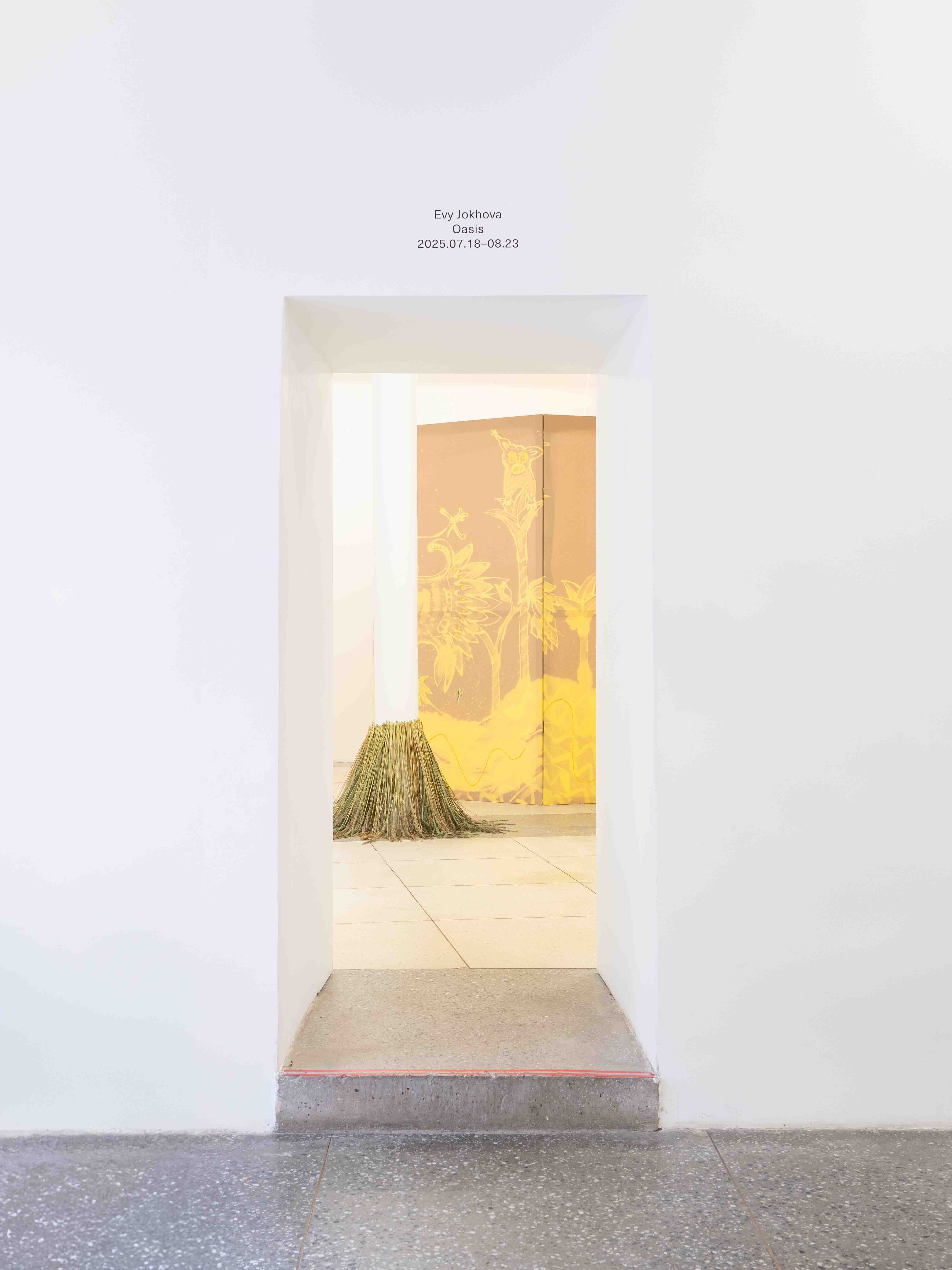

A garden begins with an enclosure, a line drawn to create a space apart. Within its bounds, the world can be re-ordered. It is a place of refuge and a site of cultivation, where the personal and the communal, the wild and the tamed, the mundane and the mythological can intertwine. In Oasis, her first solo exhibition at Medūza, artist Evy Jokhova transforms the gallery into such a space – a sanctuary for reflection and an archaeology of imagination.

The project finds its roots in the social fabric and DIY creativity of communal gardens in the Baltic region. These are spaces of remarkable resourcefulness and personal myth-making, where private narratives are cultivated on shared ground. Jokhova’s interdisciplinary practice has long investigated the dialogue between social anthropology, vernacular architecture, and art. Here, she turns her attention to the fertile ground where everyday objects sprout into symbols, exploring how enduring folklore stories can be woven from the threads of what was and what could be.

Informing this investigation is the work of Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, whose theories on a peaceful, matrifocal culture find resonance within the exhibition. Jokhova does not seek to illustrate the past, but rather to reactivate its spirit. She applies Gimbutas’ method of “archaeomythology” – reading deep meaning in humble artifacts – to the present day, treating the contemporary garden as a living archaeological site. In this space, ancient symbols of regeneration find their modern counterparts in the mass-produced as well as artist’s handcrafted objects, creating a dialogue between the deep time of prehistory and the vibrant vernacular of a Baltic courtyard.

The gallery is transformed into a landscape populated by these new relics. At the entrance, a quilted textile collage acts as a playful emissary. The piece unites elements from Jokhova’s previous work on Estonian mythology with the current context, creating a narrative in which Estonian gnomes, in a nod to the travelling gnome in the film Amélie, visit the communal gardens of Lithuania. Elsewhere, a large, dinosaur-like egg stands as an artefact of a speculative myth, its form both familiar and fantastical. This symbol of deep time, however, is presented with a sense of irony: it sits atop a kitschy, mass-produced garden frog statue purchased from “Senukai”, Lithuania’s largest chain of DIY and gardening superstores. This gesture is central to the exhibition’s logic, upending the distinction between a profound, handcrafted myth and an everyday garden ornament. It captures the blend of high creativity and consumer kitsch that characterises the resourceful, bricolage aesthetic of the communal gardens. These objects are complemented by a collaboration with woodcarver Linas Žulkus: a photograph of a misty, placeless road is juxtaposed with a frame constructed from Palanga driftwood. This frame, carved with forest animals from Lithuanian folklore, does more than simply contain the image; it actively grounds it, embedding universal journey within the local narrative.

In a time marked by widespread ecological anxiety, the turn to the garden is not a gesture of escapism. Instead, Evy Jokhova’s Oasis presents this act as a potent model for resilience and regeneration. Here, the garden is posited as an act of poetic (resi)stance, a space where mythmaking can be cultivated. This alchemy, fusing ancient cosmology with the vibrant, living practice of the communal garden, suggests that the creation of myth is not a relic of the past, but a necessary activity to be cultivated in the here and now. Functioning as a seed planted in the fertile ground of the gallery, the exhibition is a reminder that in the simple, generative act of tending to a place, we engage in the fragile art of world-making, creating a refuge where new narratives can take root and grow.

Paulius Petraitis

flawless world / what lies beneath

by Ann Mirjam Vaikla

I hear my own footsteps on the shedding asphalt, where weeds push through the cracks. Terns circle high above my head, making soothing, yet slightly alarming sounds in the wide blue sky, where not a single cloud can be seen. The warmth of a late summer day makes the air feel heavy on my cheeks and collarbones, as the wind keeps gushing over the urban landscape. Wherever I look, I see grey apartment blocks with their many windows, all covered by faded patterned curtains, shielding the interiors from the burning sun. I am mesmerised by the silence of this seemingly solitary, yet deeply communal place. I decide to sit down on the edge of the pavement, in the shadow cast by one of those architectural giants, Khrushchevkas.

I find myself staring at a strangely composed scene unfolding in front of me. In the midst of violet garden pansies, intermixed with weeds such as dandelions, nettles, and plantains, strange-looking figures have found their place. I see a gleaming white, sculpture-like object that at first resembles a swan, but with a seashell instead of a head, wide open, with a fake pearl resting in its centre. Next to it stands a shape depicting a nude woman (or is it a toad?), which enigmatically appears to consist of a pair of arms in place of legs––and this time, a fountain sprouting from her head.

I begin to notice how these two hybrids, the most visible at first, are surrounded by several others. Oddly assembled creatures are accompanied by bricks laid in circles to border the flowerbed, old tree trunks topped with flowerpots, and rubble edging the entire composition, all decorated with self-made sculptural pieces of ladybirds and colourful mosaics. I find myself thinking that this kind of carefully composed communal garden scene could appear anywhere in the suburbs of cities in the Baltic region, or perhaps across Eastern Europe at large.

*

In this layered composition of clutter, creativity, and care, the garden begins to feel less like a static space and more like a living body—one shaped by many hands, unfinished thoughts and doings over time. This resonates with Erin Manning’s insight that “A body is a field of relation out of which and through which worldings occur and evolve. We know neither where a world begins nor where a body ends.”[1] In the context of communal gardens, the notion of a body as a relation-scape, rather than an individual entity, becomes evident through a gathering of visual gestures––or through what the artist Evy Jokhova, in the exhibition Oasis, termed ‘emotive craft’. Each element within the compositions of sculptural hybrids and decorated flowerbeds first appeared as a singular expression by various individuals inhabiting the mundane urban landscape of apartment blocks, and the in-between outdoor spaces, between buildings, parking areas, rubbish bins, and playgrounds. Over time, these visual gestures found companions, as new elements were added. One might even have found it important to maintain or elevate the existing body of work simply by fixing cracks, adding an extra layer of paint, or, more boldly, by introducing a new feature, which explains how an oversized fake pearl ended up in an open seashell, placed atop a swan-looking hybrid.

Worlds are created and invented––but not only that: passers-by begin to cohabit these worlds in turn. “What is at stake in the field of relation is how the relation evolves, how it expresses itself, what it becomes, what it can do. The relation can never be properly called human. It may pass through the human or connect to certain human tendencies, but in and of itself, it is always more-than-human,”[2] Manning continues. The notion of the more-than-human extends beyond anthropocentric agency—beyond animals, plants, ecosystems, or weather—into the realm of subconscious worldbuilding that can only emerge hand in hand with storytelling. This resonates with the central question of the exhibition: how myth inspires objects, and how, in turn, objects give rise to new myths—unfolding multiple narratives and evoking the notion of what lies beneath the seemingly flawless world. These sculpture-like objects here are not merely things to be used or owned, but carriers of potential—active participants in storytelling loops that link the imagined with the real, the intimate with the collective, and the human with the more-than-human.

One might ask: what are these gardens (or field-scapes?) and myths advocating for, and in what ways might they shape our lives across generations? Gardener and thinker Gilles Clément has proposed the concept of the Jardin en Mouvement[3] (Garden in Motion), which characterises the garden not as a finished composition, a controlled territory, but as a space of constant change. “Birds, ants and mushrooms recognise no boundaries between territory that is policed and space that is wild.”[4] Communal gardens, where gardening is also understood through playful hybrid-making, visual gestures, or ‘emotive craft’, offer space to learn of nonviolent coexistence. These become sites of social healing across neighbourhoods, enabling their inhabitants to leave behind the compartmentalised, and standardised livelihoods shaped by a legacy of top-down modernist planning.

Perhaps these are not merely gardens, but urban rehearsals for other ways of being—ways that resist reduction, and the conversion of life into globally aestheticised commodities and experiences.

[1] Erin Manning, The Minor Gesture, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), p. 191.

[2] Manning, The Minor Gesture, p. 191.

[3] Gilles Clément, The Garden in Motion: From the Valley to the Planetary Garden, (Paris: Sens & Tonka, 1991).

[4] Gilles Clément, “In practice: Gilles Clément on the planetary garden”, The Architectural Review, accessed June 20, 2025, https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/in-practice/in-practice-gilles-clement-on-the-planetary-garden

Image credits Laurynas Skeisgiela